Owing to the screen size of your device, you may obtain a better viewing experience by

rotating your device a quarter-turn (to get the so-called "panorama" screen view).

|

This page updated for 2022.

|

Click here for the site directory.

|

|

Please consider linking to this site!

|

Click here to email us.

|

Onions

(Allium cepa)

Cultivars

[There are separate pages here on scallions, shallots, and leeks.]

Bulb Onions

(These are what most people think of as just “onions”, and they are frequently surprised to find that there are other sorts, some once very popular.)

“All good cooks of this one opinion: no dish savory without an onion.” We forget now the exact provenance of that centuries-old saying, but we agree heartily (or at least one of us, the one who was not as a small child fed onion juice and whiskey as a cough syrup, does).

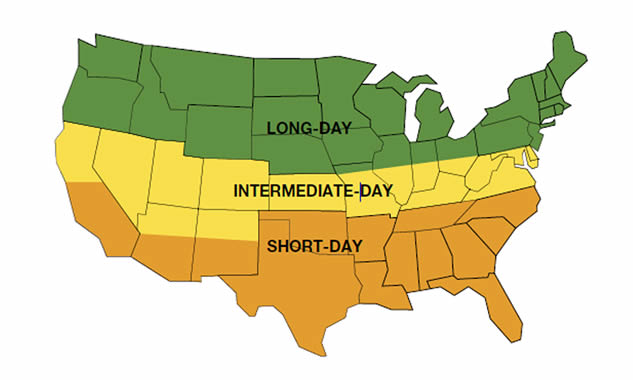

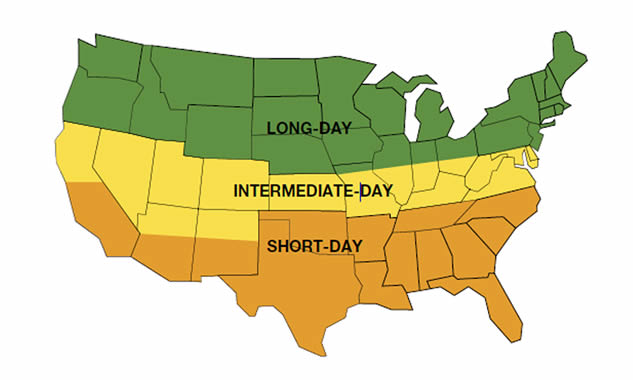

Little by little seed catalogues are starting to acknowledge the crucial but for long unpublicized fact that you cannot grow any onion anywhere. The broad division is into “short day” and “long day” types, with some adding a third class called “intermediate day” onions.

Those divisions exist because onions are day-length-sensitive (or, in truth, night-length-sensitive). The plants sense the length of the day (or, again, actually of the night) and use that datum to “decide” when to do what in their plantly lives.

Here, from Dixondale Farms, is a a handy map:

The two types differ not only in daylength sensitivity, but in culinary and keeping qualities. The long-day onion class (also called “American”) is substantially stronger-tasting, and also is of very much better keeping quality than the short-day (or “European”) sort. The common apprehension that short-day types—such as the famed Vidalia—are “sweeter” is quite wrong: they are milder—less pungent—which is not at all the same thing; in fact, the long-day types have more actual sugar, and in consequence actually cook up sweeter (cooking minimizes or reduces the sulfur compounds that give onions their pungency). In any event, we really have no choice: at our latitude, we must grow long-day onions.

Connoisseurs (we will strive mightily to avoid the buzzword gourmet) apparently attach real significance to particular varieties of onion (Nero Wolfe, passing through his kitchen, takes a nibble of a raw onion his cook is slicing and asks “Ebenezer?” implying that a discriminating palate can tell one variety from another from but a taste, rather like a wine). But meaningful, realistic flavor comparisons between particular cultivars of onion is essentially nonexistent (there is plenty and plenty of published evaluation, but none we have seen rises to the level of “meaningful, realistic”). But we can at least deal in generalities about the types.

There are three broad classes of onion, identified by color: white; yellow (which includes a sub-class called “brown”); and red. It is consensus agreement that the yellow/brown class is the most pungent when raw but cooks up the sweetest, and is thus best for cooking purposes. The red class is milder, though often still described as “pungent”; for those who are timid about onion flavor, red is probably the best for use raw, as on sandwiches or in salads. The white class seems to be a mediocre version of the yellow class, and is valued, if at all, for its color, for the sort of cook who uses white pepper instead of black (though they taste identical) because the black specks are offensive. (Whites are also reportedly more difficult to grow than yellow/browns, being more susceptible to various diseases.)

Another profoundly important datum is keeping time: the yellow/browns keep very much longer than do the reds (the browns keep longest of all). That is important when one is growing one’s own instead of picking up a new supply at the supermarket every week. The best-keeping browns can, some say, under ideal conditions last close to to a full year, or at least till close to the time when “baby” onions can be taken from the next crop; the longest-keeping reds can go into the following spring or, it is said of some, even early summer.

Note that we deal here only with open-pollinated cultivars. Ask a lot of gardeners about long-keeper onions and you will often hear about Copra (brown) and Redwing (red), both hybrids. But the OP types we discuss here are usually thought to be about as good, both as to keeping quality and as to eating quality.

“Ideal conditions” for onion storage—temperature just over freezing, humidity circa 70%—are not always readily achieved. Most folks hang their storage onions in string bags somewhere indoors (where “indoors” may well be a garage); the ideal, which few can manage, is a drying shed or a root cellar. (There are occasional reports of some brown onions lasting even over a full year—one reported an amazing two years.)

There is also a charming onion sub-class called “buttons” or, more commonly, by their Italian name, cippolini. These are not “pearl” or “cocktail” onions; they are smaller, and quite delightful. They are said by some to be hard to grow, but if you have space they are worth trying for fun.

Thus, the home grower wants to grow mostly the best-keeping brown available, perhaps supplemented by a small amount of the best-keeping red available for use raw during its keeping-time window.

Massive review of the literature available on the web and on usenet suggests that the best yellow/brown “keeper” is the open-pollinated Newburg, seeds not common but findable. (That’s it illustrated at the left.) It matches the performance of hybrid “Copra”, considered the gold standard for onion storage.

Some red onions of the long-day type also store decently, though not so well as yellow/browns. Facts beyond vague statements of “good keeper” are hard to come by, but we’ve done the grunt work, including finding comparative keeping studies. From all that, the cultivars that emerged as almost surely the best-keeping open-pollinated red onions are:

Rossa di Milano: everyone says “sweet” and “tolerates cool weather well” and keeps quite well— some say into the next spring and perhaps till May or even early June, though it’s seedsmen who say so. Probably best red keeper now available, unless it’s the one below. Some describe it as “hot” (though mildly so).

Red Wethersfield: an heirloom standby; flavor fine but pungent, not sweet; one grows reds for use raw, in salads or on sandwiches, so if you like ’em strong, this is it—if not, not. (Once actually used as currency in the town of Whethersfield, Connecticut.)

(The type Redman was apparently thought the best of all and was very popular, so of course it has now disappeared from seedsmen’ catalogues in the U.S. That sort of nonsense is all too common in these days of rampant hybrids….)

Incidentally: it seems to be consensus that seed-grown onion both grows better and tastes better than onion from “sets.”

Cipollini

Despite the fact that the Italian onion type called “cipolinni” (literally, “little onions”) is often compared to what in the U.S. are known as “pearl onions”, the differences are significant. “Pearl” onions are any white (or even yellow) onion harvested when still pretty small; cipolini are a particular kind of onion (a long-day, long-keeping type) with a distinctive set of qualities. They will not be a large fraction of anyone’s onion crop, but they are a pleasing specialty with many virtues and should be included in any vegetable garden.

Here’s a link to a University of West Virginia trialling of some cipollini types.

The Borrettana cipollini seems to be the preferred white/yellow type, from that study and from the general literature. For a red cipollini (fairly new in U.S. seedsmen’s listings), the most likely candidate is the Di Genova, scarce but findable in the U.S. (we don’t usually name particular seedsmen, but for this type try Seeds of Italy, which sells the Franchi brand of seeds).

Potato Onions

Besides the standard bulbing onion described above (and such onion variants as shallots and scallion types), there is a kind once well-known and popular but now nearly faded to an obscure memory: the “potato” (or “multipler”) onion. They are a specialized sub-species of the ordinary A. cepa bulb onion, being Allium cepa var. aggregatum. And these little guys should remain of real interest to the home gardener; as the Wikipedia article on them says, “It is remarkably easy to grow, keeps better than almost any other variety of onion, and is ideal for the home gardener with restricted space. It was very popular in the past, but—like many old varieties—it has been passed over in favor of types more suitable for mechanical harvesting and mass marketing.”

Perhaps the most important thing about potato onions is that they are essentially a perennial onion. They don’t actually each stay alive forever, but the way one grows them assures a perpetual supply, and almost year round. Read on…

The potato onion is reputedly a superb “keeping” onion (and the only good-keeping onion that can be grown in short-day latitudes, which is about the southern 2/3 of the U.S.). It is just a little smaller than the standard bulb onion (running from 2 to 4 inches in diameter), but still eminently useful. Their flavor is often said to be as sweet or even sweeter but a little milder than “standard” onions, and with a hint of garlic as well—indeed, they sound much like shallots (to which they are closely related).

There is a nice short summary about them [archived PDF document] from the University of Wisconsin available on line; but it propagates a very common and serious mistake about potato onions that we need to address right now.

The offending line is “Select and save the biggest and best bulbs for replanting in the fall.” Since this type can sometimes be quite small, one would think that good advice, but it’s not. The curious rule with these is apparently: Planting a small bulb gives a single big-bulbed plant; planting a big bulb gives a cluster of small bulbs. Many first-time growers, unaware of that, do just what that brochure says, then are vastly disappointed by the small bulblets they grow out. Keep enough going that every year you have a mix: small bulblets planted to give you your eating onions, and some big bulbs planted to give you your next season’s small seed bulblets.

Once upon a time, one could find all three onion colors—red, yellow, and white—of potato onions in seedsmen’s catelogues; no more. Now they are hard to find at all (so far as we can see, only a very few suppliers carry them, all as yellow varieties with no named cultivars). One of those houses is Southern Exposure Seed Exchange, and what they say about the type is well worth reading:

Heirloom potato onions enjoyed widespread popularity before the turn of the century. Nearly every gardener grew potato onions and they were available in yellow, white, and reddish-brown varieties, the yellow being most common…Each bulb cluster of potato onions may contain many bulbs, averaging 2 to 2½″ in diameter. When a small bulb (¾") is planted, it will usually produce one or two larger bulbs. When a large bulb (3" to 4") is planted, it will produce approximately 10 to 12 bulbs per cluster. These bulbs of various sizes may be used for eating, storing, or replanting. By replanting a mixture of sizes you will have plenty of sets for next yeards crop and plenty of onions for eating during the year. Potato onions can increase 3- to 8- fold by weight each year depending on growing conditions. Potato onions store better than most seed onions, and individual bulbs can be grown in flower pots to produce a steady supply of green onions during the winter. [emphasis added]

The discussions below are entirely about standard bulbing onions. For cultural information on potato onions beyond what appears above, just follow the directions pertaining to shallots, except to perhaps increase the planting spacing to 6" or so. (The cultivariable site has a good page on potato onions, including growing instructions.)

“Walking Onions” (aka “Tree Onions”)

These are actually a distinct sub-species, now classed as Allium x proliferum (formerly variously classed Allium cepa var. proliferum, Allium cepa var. bulbiferous, or Allium cepa var. viviparum) from the other onions we discuss here (which are plain Allium cepa). They are a cross between Allium cepa, the ordinary cultivated onion, and Allium fistulosum, the so-called “Welsh onion” or scallion (see our page on scallions).

These are called “Walking Onions” (or, often, “Egyptian Walking Onions” or just “Egyptian Onions”) owing to their peculiar method of multiplying: when the topsets become heavy enough, they pull the plant over to the ground, where—if the soil conditions are right—the fallen topsets take root and form new plants! (Thus making the species effectively perennial!)

For these, the edible portion is not an in-ground bulb, but rather “bulblets” that set in clusters at the tops of the stalks. There is a ton of information about these at The Egyptian Walking Onion web site (a commercial grower), including numerous photos. Another wonderful resource is the University of Wisconsin’s Egyptian Walking Onions psge.

We’re going to try at some point to establish a bed of these. They can be harvested for use as scallions, plus the bulblets can be used as mini-onions; the bulbs’ culinary quality is said to be decent but not outstanding—the trusty Vilmorin guide (1885) says of them “tolerably agreeable to the taste, but rather deficient in delicacy of flavour“—but they are also said to make great pickled onions. Indeed, all parts of the plant have edible uses. (They are grown from purchased bulblets, never seed.)

If all else we plan for onions works, we probably don’t need these, but they make a nice novelty and reportedly are both very hardy (they will grow up through snow) and prolifically productive. While there are identified cultivars, almost all seedsmen handling them sell them as generics; what is said to be an “improved” strain is called Catawissa [archived copy], a red/brown type supposedly a little hardier and more productive than the original. (Though “hardier” is hard to conceive!) The famed William Woys Weaver says that this strain is “somewhat different from the others because they send up topsets from topsets, creating the image of plants growing out of plants. These hybrids are strong growers, often attaining 4 or 5 feet in height, and always in need of staking as a precaution against heavy summer rains.” There is reportedly also a Red Catawissa cultivar. Good luck finding plausibly identified cultivars from the seedsmen (Territorial appears to offer something that might be that Catawissa Red; others have it for sure).

Planting

This discussion is only about standard garden bulb onions; for any other kinds, look up their specific requirements.

Best results, in quantity and quality, are from onions grown from seed, not from “sets”. But beware: onion seeds are notoriously short-lived. If you aren’t saving you own seed annually, don’t try to be cheap and use last season’s leftovers—get fresh seed every year.

Timing

Onions from seed can be handled as indoors-grown seedlings transplanted out, or as direct-seeded. If you opt to direct-seed, which certainly saves a lot of fuss, you need to practice “winter sowing”; the Savvy Gardening site has a nice description of the winter-sowing process, which we will not repeat here: just follow the link (then scroll down the page a bit, to the heading My favorite method: Planting onion seeds via winter sowing). Basically, it reproduces how onions grow in nature.

We will note, from that link, that you start planting onion seeds via winter sowing anytime between early December and mid-February; you then transplant on the classic day “as soon as your soil can be worked”. (Our calendar assumes March 15th.)

Onions grow by first developing their “tops” (above-ground greens), then—when triggered by daylength—setting their bulbs. When they begin to set the bulbs, the tops stop growing. There are two utterly vital points involved here. Rule: an onion plant’s bulb will never be bigger than its top. Corollary: grow tops as big as you can get them before bulb formation is triggered. That’s why we transplant them “as soon as your soil can be worked”.

Starting Seedlings

Again: the fine folks at Savvy Gardening have laid it all out nicely: just follow their instructions.

The Bed

Onions prefer a sunny, sheltered position in loose, well-drained soil of high fertility with plenty of organic matter worked in. Onions are sensitive to highly acid soils, and grow best when the pH is between 6.5 and 6.8.

Transplanting Out

When setting out your transplants, be sure to only just cover their roots with soil, because the bulbs grow on top of the soil. (One source said: “Instead of planting them sticking straight up, we lay them down in a trench and move the soil back over their roots. In about 10 days they’re standing up and growing along strongly.”)

Space onions at about 4 inches; having a deep-dug or raised bed is good for them, as for all vegetables. Onions crowded too tight will not develop well.

Growing

“Hot” (harsh, overstrong) onions are usually a result of insufficient watering. Onions have a shallow, meager root system, and need their soil kept continually moist (but not flooded!). They want light but frequent watering—a soaker hose should work well.

But…as the plants approach maturity, the bulbs stop growing and start putting on skin; that is the time to stop watering altogether and let the bulbs finish in dry soil. (And pray it doesn’t rain.)

Onion beds need to be kept very well weeded, because weeds easily out-compete onions for water and nutrients, owing to onions’ weak root systems. But—also because of that shallow, weak system—be sure to cultivate shallowly with a careful hand and eye, lest you harm the onions themselves.

Since weeding will get you up close and personal with your onions, use the opportunity to keep a close eye out for any flower stalks that might appear—they shouldn’t, but they might. If you see any—search out and check some photos for positive identification—just pinch them off at the base (else your onion will bolt and be useless).

While onions like rich soil, avoid using any high-nitrogen based liquid fertilizers when your onions are well along, lest their growing efforts go into their leaves instead of their bulb.

Pull onions when the tops have gone brown and fallen over. Some gardeners break the tops and push them over to try hastening development, but that should not be necessary and may be a bad idea; just grow them and let them do their thing. Don’t puncture them in extracting them from the soil. After pulling them, let them dry in the sun for a day or so, then cure and store them as you would garlic or shallots.

More

Relevant Links

Besides any links presented above on this page, the following ought to be especially helpful.

Odds and Ends

Biology

Onions are of the Alliaceae family, the alliums (till recently called the Lilliaecae family). Besides such obvious relatives as leeks, scallions, and garlic, the onion’s kin include lillies and hyacinths.

History

We won’t try to re-invent the wheel; here is an excellent on-line history of onions.

Envoi

If you’re here, you probably like onions; but if you don’t, you can look in on the Official Facebook page of the Anti-Onion League.

Return to the top of this page.

If you find this site interesting or useful, please link to it on your site by cutting and pasting this HTML:

The <a href="https://growingtaste.com/"><b>Growing Taste</b></a> Vegetable-Gardening Site

—Site Directory—

Search this site, or the web

-

Background Information

about the purposes and design of this site

- Site Front Page

-

Introduction

- An Apologia: why one should cultivate one's garden

- Deep-Bed Gardening (forthcoming)

- Container Gardening (forthcoming)

- Vegetarian and Organic Considerations (forthcoming)

-

Recommended Crops for a home garden, by variety

-

Gardening information and aids

-

Miscellaneous Information of interest to the home gardener

Since you're growing your own vegetables and fruits, shouldn't you be cooking them in the best way possible?

Visit The Induction Site to find out what that best way is!

|

If you like good-tasting food, perhaps you are interested in good-tasting wines as well?

Visit That Useful Wine Site for advice and recommendations for both novices and experts.

|

|

This site is one of The Owlcroft Company family of web sites. Please click on the link (or the owl)

to see a menu of our other diverse user-friendly, helpful sites.

|

|

Like all our sites, this one is hosted at the highly regarded Pair Networks,

whom we strongly recommend. We invite you to click on the Pair link for more information on getting your site or sites hosted on a first-class service.

Like all our sites, this one is hosted at the highly regarded Pair Networks,

whom we strongly recommend. We invite you to click on the Pair link for more information on getting your site or sites hosted on a first-class service.

|

|

All Owlcroft systems run on Ubuntu Linux and we heartily recommend it to everyone—click on the link for more information.

|

Click here to send us email.

Because we believe in inter-operability, we have taken the trouble to assure that

this web page is 100% compliant with the World Wide Web Consortium's

XHTML Protocol v1.0 (Transitional).

You can click on the logo below to test this page!

You loaded this page on

Monday, 31 March 2025, at 13:14 EDT.

It was last modified on Wednesday, 5 January 2022, at 04:31 EST.

All content copyright ©1999 - 2025 by

The Owlcroft Company